From THREE DISCOURSES AT THE COMMUNION ON FRIDAYS (1849)

On hypocrisy and sincerity.

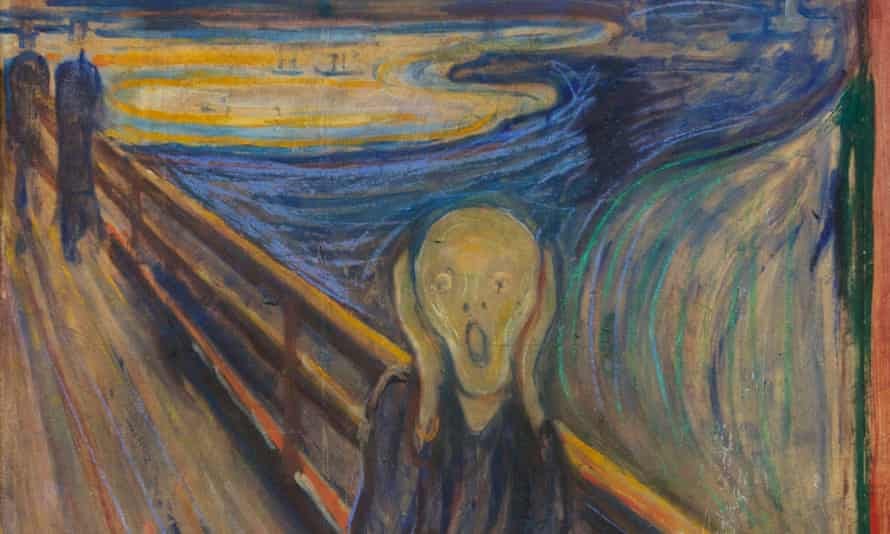

“What hypocrisy (Hykleri) would there possibly be in the scream of someone for whom in distress at sea the abyss opens, even though he knows that the storm mocks his frail voice and that the birds out there listen to him indifferently; he cries out nevertheless—to that degree his scream (Skriget) is true and truth. So also with what in an altogether different sense is infinitely more terrible, the conception of God’s holiness when a person, himself a sinner, is alone before it—what hypocrisy would there be in this scream: God, be merciful to me, a sinner! If only the danger and the terror are actual, the scream is always sincere, but more than that, God be praised, it is not futile either.”

A creative and perceptive exegete of the Bible, Kierkegaard was fond of using biblical stories and images for philosophical reflection—a tendency that became increasingly pronounced as his authorship evolved. In November 1849, just a few months after publishing The Sickness unto Death, Kierkegaard released Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays, a short collection of discourses intended for reflection prior to receiving Communion, particularly at the quiet Friday services. The second discourse concerns Luke 18:9-14, in which Jesus contrasts the comportment of a Pharisee and a tax collector in temple: the former is proud of his righteousness, the latter humbled by his sin. And yet, in what was likely a surprising reversal to Jesus’ first listeners, it is the tax collector who has the better grasp of the human condition: “I tell you, this man [the tax collector] went down to his house justified rather than the other: for every one that exalteth himself shall be abased; and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted” (Lk 18:14).

Kierkegaard had struggled with this passage since his student years. As he remarks in a 1839 journal entry, “The confusing thing about us is that we are simultaneously the Pharisee and the publican.” It is perhaps for this reason that Kierkegaard’s discourse attends less to the figures themselves than to their spatio-temporal location in the temple. Though the Pharisee stands by himself, he keeps his eye on the tax collector: thus he is engaged in a comparative assessment of virtue, and this horizontal comparison has blocked his ability to enter into a vertical encounter with God. In contrast, the tax collector stands far off (Lk 18:13), paying attention to no one else and thereby confronting God in truth. Both men are in the same space, but, as Kierkegaard explains in the passage above, only one experiences the “danger and terror” of the divine presence.